This particular episode was an interview with attorney Ed Greenberg and commercial photographer Jack Reznicki, the guys behind a book and website called The Copyright Zone. I won't bore you with details to convince you, but trust me when I say Ed and Jack have considerable experience litigating copyright issues related to photography with major, well-known clients, and they know their stuff. They've also spent a lot of time sharing that wealth of knowledge with photographers in various forums over the years, such as Steve's podcast. And after listening to their interview with Steve and subsequently buying their book, I quickly realized how little I actually knew about copyright, and more importantly, just how much bad information I was relying on from questionable sources on the web.

And so, this blog post.

Let me start by getting one thing clear: I'm not a lawyer. I don't claim to be anything more than a regurgitator of legal advice given by real lawyers, and I highly recommend that if you want reliable advice, you seek out the counsel of a local, reputable litigator of intellectual property law. (As Ed would say, local and litigator are the key words there.) And of course, check out Ed and Jack's web site and book. Use my feeble interpretations at your own risk - you're better off going straight to the source! And of course, I live in the United States, so anything said here only applies to the U.S. copyright system.

Ok, now that we've got that out of the way, here's an overview of what I've gathered from Ed and Jack and how it pertains to my little print store, and what I think is important for concert photographers to understand before trying to sell prints online.

What Does Copyright Mean To Photographers?

Let's start with the basics. If you're a freelance photographer and you take some photos, and you haven't signed anything that gives your copyright for the job to another party (such as with a Work For Hire agreement) and you're not employed by someone primarily to be a photographer, then you own your copyright. It's yours, period. And assuming you haven't signed anything that restricts your ability to exercise your copyright or assigns rights to other parties, then you alone control the image, you decide how it can be used and who can use it. You alone can profit from it.

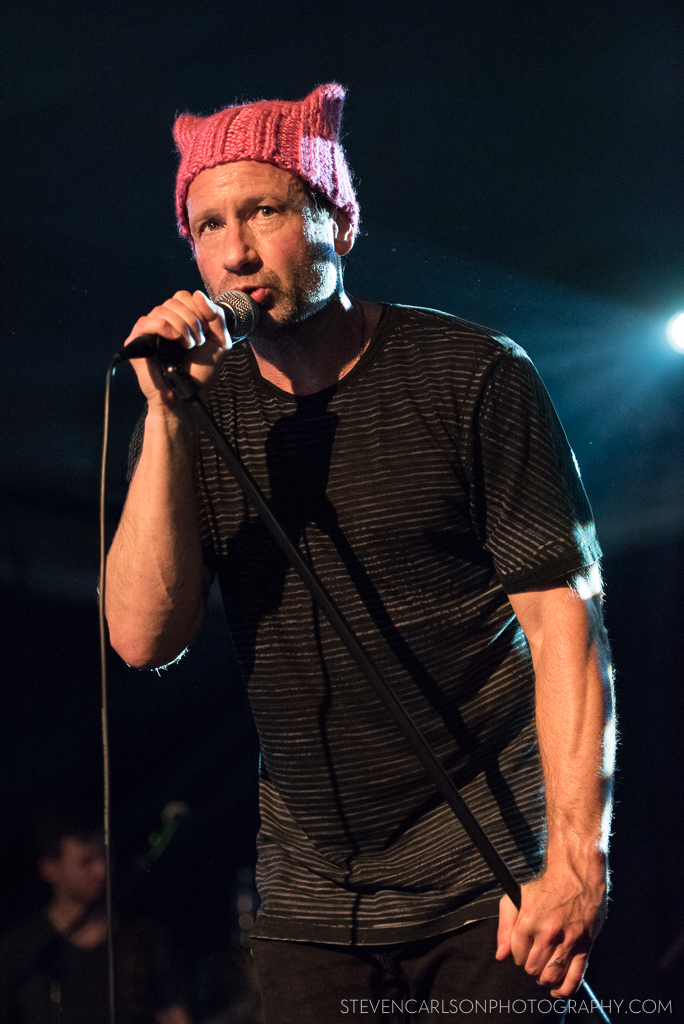

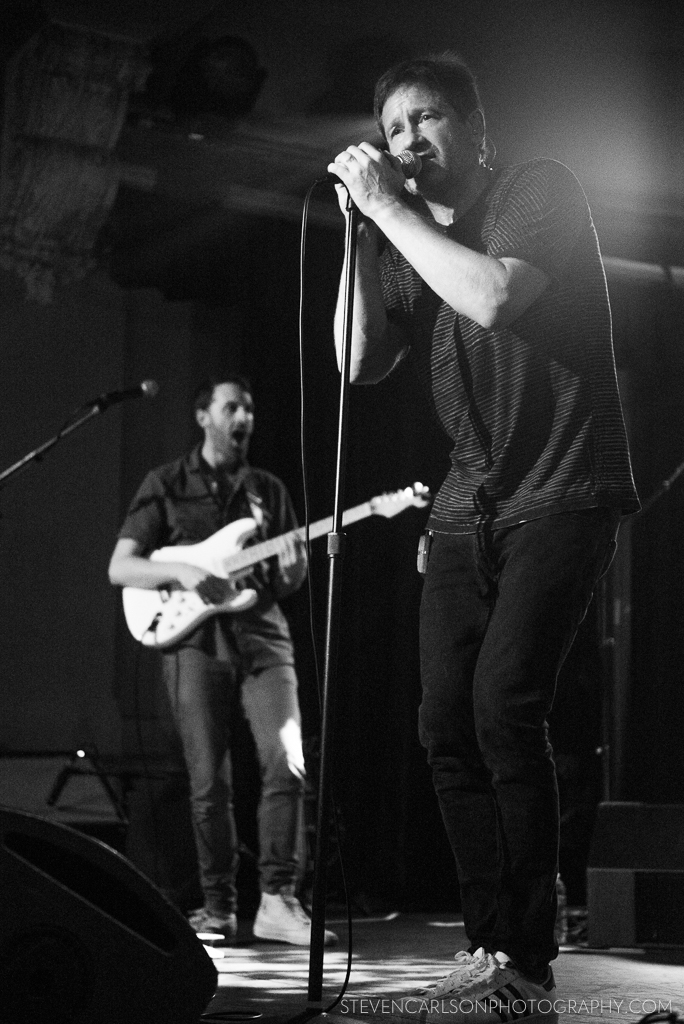

So, let's say for the sake of a very simple example, you're a concert photographer and you've requested and been approved to shoot your favorite band's show as a freelancer. You haven't signed any sort of agreements or releases with a publisher or the band. You show up at the venue, you take photos for the first three songs, and you go home. Pretty simple, right? You own the copyright, the photos are yours, you can do whatever you want with them. Right?

Ah, but not so fast.

Types of Use and Model Releases

So you've just taken the most amazing shots of your favorite band. Your shots are the best you've ever taken, you know the band's fans will love them. You have visions of licensing your images to Rolling Stone, or making t-shirts and prints out of them, and making bank. Can you do it? Yes and no.

The fact is, you own the copyright, but you've been taking pictures of people - that is, the band. And when people are in your photo, things get a little more complicated. (Same goes for some venues too, though we won't go into that.) Chances are you haven't requested (and are unlikely to receive) a signed model release from the band members. So right off the bat, you're limited in what you can do with your photos, because they include someone's likeness, and their right to profit from their own likeness is protected. You can license your images for editorial use (e.g., publication in newspapers, magazines and other forms of media) because the images are newsworthy and protected by the First Amendment, but you won't be able to use them for commercial use like t-shirts, posters, mugs, etc. Advertising is considered commercial use too, so you can't license your image to a guitar company who wants to run a magazine ad featuring your shot of the band's guitarist. To use the shots for commercial use, you're going to have to get the subject of the photo to sign a model release.

Ok, fair enough, so you won't print up t-shirts and try selling them on eBay. And it turns out nobody, much less Rolling Stone, has interest in your shots, so editorial licensing isn't happening. You still want to make a few dollars off your shots, however, because you've just got to buy a fancy new Nikon D850 soon. So what about selling prints directly to fans?

The Gray Area of Fine Art Prints

Here's where things get a little murky. Most concert photographers understand that they can't print up t-shirts with their shots, but many believe it's perfectly fine to sell prints. There's a prevailing sense that there's just something intrinsically different about prints, that printing a photo on paper is somehow more moral than printing the exact same image on a t-shirt. I think it comes down to a feeling that while t-shirts are clearly a product, prints are a work of art.

But what makes a print "art"? The internet is littered with armchair lawyers offering up advice on what you can and can't sell when it comes to prints, all driven by this question. Some say there's no restrictions at all if you hold the copyright. Others say you're fine as long as you produce "fine art", which to them means that you use high quality papers and archival quality pigment-based inks for giclée prints, or other high quality photographic processes. Some say you have to sign and number your prints to qualify, while others say don't bother. Most people confidently say you're in the clear only as long as you don't produce more than a magical number of 250 copies. So what's the truth?

According to Ed and Jack in their book The Copyright Zone:

...the Copyright Law defines a "work of visual art" in part as: "A painting, drawing, print or sculpture, existing in a single copy, in a limited edition of 200 copies or fewer that are signed and consecutively numbered by the author..."

So there you go. 200 or less, signed and consecutively numbered, is what the law says qualifies for protection as "visual art", according to Ed and Jack.

So is that it? As long as you produce less than 200 copies and you sign and number them consecutively, it's fine art and you're in the clear? Not quite.

In The Copyright Zone, the authors use the example of Nussenzweig v. diCorcia to illustrate just how thorny "fine art" print sales can be. In this case, photographer Philip-Lorca diCorcia captured images of random people on the streets of New York, and the images were displayed in a gallery and sold in limited quantities for upwards of $20,000 each. One subject, Erno Nussenzweig, had not signed a model release and objected to the exhibition and profiting off of his image. He sued, and lost. Why? According to the Ed and Jack, it's because the court ruled "the photograph of Rabbi Nussenzweig was considered a work of fine art by a recognized artist, printed in a very limited edition, and exhibited in a widely recognized art gallery." (Emphasis mine.) In her decision that diCorcia's work should be treated as a work of art and not commerce, New York State Supreme Court Justice Judith J. Gische specifically wrote that "Defendant diCorcia has demonstrated his general reputation as a photographic artist in the international artistic community."

The words "recognized" and "reputation" are the key words here. In a nutshell, who you are known to be matters as much as what you're selling. diCorcia's work was rightfully considered art and therefore protected speech because of his reputation and the way his prints were exhibited and sold.

Conversely, it would therefore seem that normal, average photographers can't sell prints of people who haven't signed a release, call it "fine art", and expect to be shielded by the law if the subject complains, at least in New York. Fine art photography isn't just defined by the quality or quantity of the work you produce. In a court of law, if you don't have a model release you may have to demonstrate your credentials as a fine art photographer in order to be protected.

This is a big point that I suspect most concert photographers would be surprised by. If you are sued by a band that objects to you selling prints of them and you don't have a release, your credentials as a fine art photographer could be scrutinized. You could easily lose your case if you can't convince the court that you deserve artistic protection by demonstrating that you've displayed your work regularly in art galleries, books, exhibitions, etc. And losing your case could get mighty expensive.

For most concert photographers, I expect this is a pretty tough hurdle to get over, as most photogs in the pit are probably shooting part-time, aren't widely known in the art world, and aren't displaying their work in galleries on a regular basis if at all.

For me, this point put my print store launch on hold while I considered my next move.

But Really, What Are The Chances You'll Be Sued?